Why the Deuterocanon / Apocrypha Is in Some Bibles and Not Others

From Scrolls to Books: A Short History of the Bible

When you’re looking at different Bibles, you may be surprised to discover that they don’t all contain the same collection of books. You might see Tobit or 1 Maccabees in one Bible but not another and wonder if someone made a mistake. Is one version correct?

Today’s Protestant Bibles have 66 books, but the first Protestant Bibles printed way back when actually had a few more. Roman Catholic Bibles include the same 66 plus another several other books, and Eastern Orthodox Bibles include all of those and a couple more.

Here’s another interesting, potentially uncomfortable truth: as Christianity has spread throughout the world, we’ve never seen a time when all Christians have agreed on the shape of the Bible. Much of the historical debate revolves around what to do with books that are sometimes called “Deuterocanon” or “Apocrypha,” and that collection is in focus here.

So, how did we get the Bibles we have today? What are the deuterocanonical or apocryphal books, and where did they come from? And if the sacred text that grounds the three most enduring Christian traditions is not the same, how does it make sense to call each version The Bible?

How Do the Protestant, Catholic, and Eastern Orthodox Bibles Compare to Each Other?

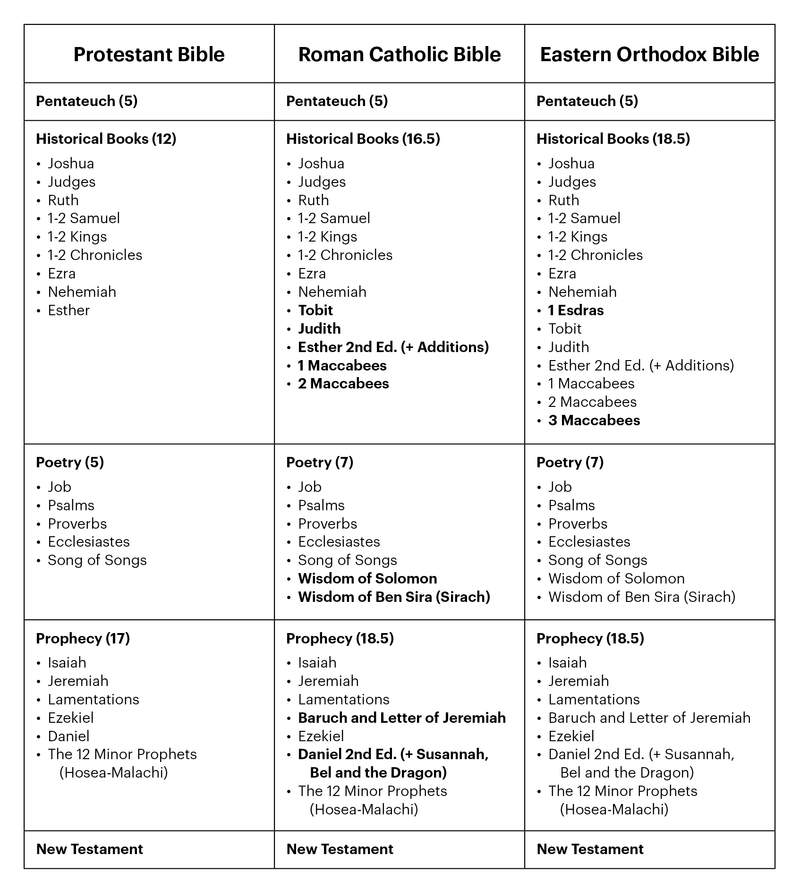

For clarity’s sake, let’s get all three Bibles in front of us for a quick comparison:

(View below image in a new window.)

This is a high-level summary chart. If you drill down further into the different expressions of the Eastern Orthodox tradition (e.g., Russian, Greek, or Ethiopian Orthodox traditions), you will find more variation. As you compare, you’ll see the same New Testament in all three traditions. The differences are found only in the Old Testament.

So, how much do these differences matter? Is it okay for Christians in one tradition to read the Bibles of other traditions? And which of them, if any, are more original? How did each of these differences come about?

We want to offer some information to help you begin to think through these questions, but one article can’t fully resolve these issues. So for those interested in going deeper, see the recommended resources at the end.

What Are the Hebrew Scriptures, and Where Did They Come From?

A few centuries before Jesus, following a 1,000-year process of writing and compiling, the Scriptures of ancient Israel were given their final shape in an organized collection—the Tanak, also known as the Hebrew Bible or Old Testament.

Tanak is an acronym for the Hebrew words Torah, Nevi’im, and Ketuvim (TaNaK), referring to the three parts of the Hebrew Bible: “Torah, Prophets, and Writings,” also called “Torah and Prophets.” Those titles come from the Hebrew Scriptures (see Zechariah 7:12; Daniel 9:10-11), and Jesus called these texts “the Scriptures” or “the Law of Moses, the Prophets, and the Psalms” (see Luke 24:27, Luke 24:44).

Beginning with Moses (see Exodus 17:14 and Exodus 24:4) and continuing forward to the prophets who lived after Israel’s exile to Babylon, the biblical authors wrote their own new works while also having access to a wide range of previously written scrolls. Sometimes they quote from and even cite these sources. A few examples:

• “The scroll of the birth-generations of humanity” (Genesis 5:1)

• “The scroll of the battles of Yahweh” (Numbers 21:14)

• “The scroll of the upright one” (Joshua 10:13; 2 Samuel 1:18)

• “The scroll of the chronicles of the kings of Israel” or “of Judah” (1 Kings 14:19; 1 Kings 14:1 Kings 14:29; 1 Kings 15:7; 1 Kings 15:1 Kings 15:23, etc.)

None of these source scrolls used by the biblical writers have survived until today, but knowing that the biblical authors compiled and arranged old material while also writing new texts is helpful. The process of writing, compiling, and editing continued for many centuries, until the Tanak came into its final form.

Each individual scroll in the Tanak has been editorially connected to the larger collection. (Check out our video on the Tanak.) Think of a museum exhibit about ancient Egypt put together by a curator who collected artifacts from different places and times and organized them in a way that takes visitors on a journey and provides a cohesive experience. The biblical authors and compilers are like that curator, and the Hebrew Scriptures are like the exhibit—a composite collection of diverse materials from many sources and authors that have been brought together into a unified whole.

The organizational work of these scribes is on display all over the Tanak, especially at the beginning and ending of major divisions in the collection. We can see their work in the comment at the end of the Torah that no prophet like Moses has yet arisen (Deuteronomy 34:10-12) and the continued hope for a Moses-like prophet named “Elijah” at the end of the Prophets (Malachi 4:4-5). Similarly, their hand appears when Joshua is portrayed at the beginning of the Prophets (Joshua 1:7-8) as fulfilling the portrait of the ideal reader of the Scriptures that opens the Writings in Psalm 1 (for more information on the overall editorial shape of the Tanak, see John H. Sailhamer, Introduction to Old Testament Theology: A Canonical Approach, p. 239-252).

Based on both biblical and historical evidence, the final shape of Israel’s scriptural collection was formed by a group of scribes and prophets in Jerusalem around the 4th-2nd centuries B.C.E., likely part of the community that returned from Babylonian exile during the time of Ezra and Nehemiah. These scribes believed the Spirit of God was speaking through these texts, revealing God’s perspective on Israel’s history. Their goal in curating this collection was not merely to preserve the past but also to offer a message of hope for the future and to inspire present-day faithfulness to God (see Psalm 119 for insight into their reverence for Scripture).

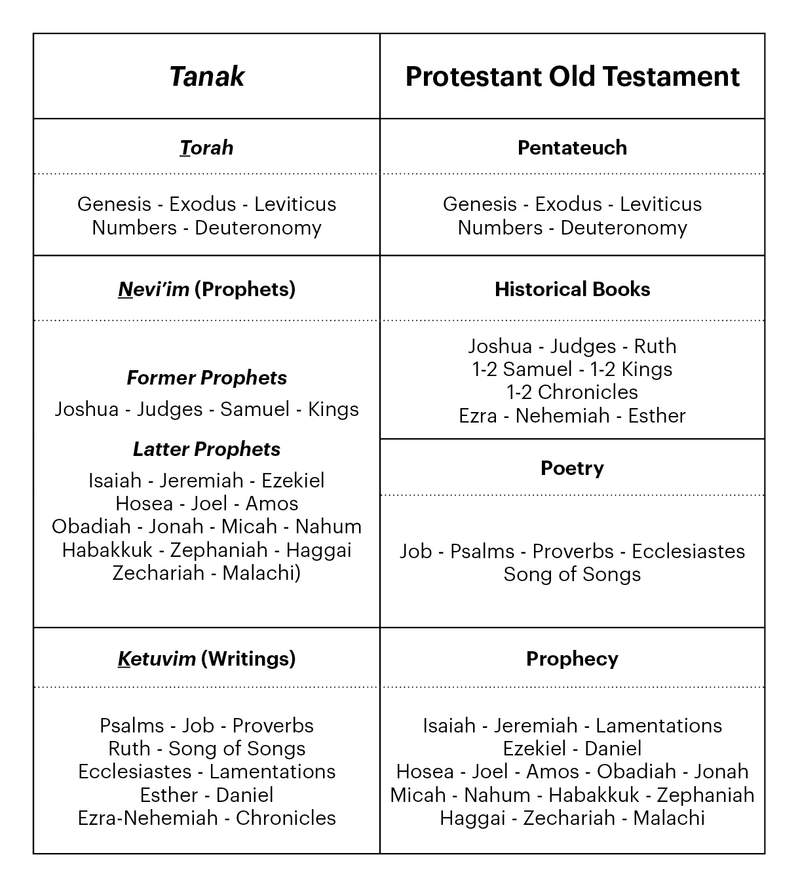

When we compare the contents of the Tanak with the Protestant Old Testament, we find the same texts, but they’re arranged differently:

(View below image in a new window.)

At first glance, these may seem like significantly different Bibles, but the differences are only in arrangement and scroll division. The actual texts included in the two Bibles are the same.

What Is the Deuterocanon / Apocrypha, and Where Did It Come From?

The Writing of Second Temple Jewish Literature

After the Tanak took its final shape, Jewish communities near Jerusalem and abroad started reading it fervently, sparking a new wave of literary creativity. They believed these texts had divine authority, and they constantly discussed and meditated on these Scriptures. As a result, some Jewish scribes began writing new texts that would expand upon key themes and ideas from the Tanak, and they wrote a lot.

This wide body of literature is today called “Second Temple Jewish Literature” because it was produced during the period of Israel’s rebuilt (second) temple in Jerusalem, which lasted from the late 500s B.C.E. to 70 C.E.

Some of these books reflect Jewish scribes experimenting with new literary styles influenced by Greek and Roman culture, while others closely imitate biblical texts. Their authors were devoted scholars—true Tanak nerds—frequently quoting from and engaging with its themes and ideas.

Here’s a (small) sampling of popular works from the Second Temple era, according to contemporary categories of literary style:

Historical Narratives

• Tobit

• Judith

• 1 Maccabees

• 2 Maccabees

Apocalyptic Visions

• 1 Enoch

• 2 Enoch

• 4 Ezra

• 2 Baruch

• Apocalypse of Abraham

• Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs

Wisdom

• Wisdom of Solomon

• Wisdom of Ben Sira (Sirach)

• 3 Maccabees

• 4 Maccabees

Poetry and Songs

• Psalms of Solomon

• Prayer of Manasseh

• Baruch

Retellings of Tanak Stories

• Jubilees

• Joseph and Aseneth

• Life of Adam and Eve

• 4 Baruch

For a full list, check out the two volumes edited by James H. Charlesworth, The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: Volumes 1-2, and also the two volumes edited by Richard Bauckham, James R. Davila, and Alexander Panayotov, Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: More Noncanonical Scriptures: Volumes 1-2.

Some of these books read like ancient commentary, addressing theological puzzles left unresolved in the Tanak. Others aim to translate and update biblical ideas for a new generation of Jews living under Greek, Syrian, or Roman rule. Since Israel’s story continued after the Tanak, much Second Temple literature reflects that ongoing history from the 4th century B.C.E. to the 1st century C.E.

The Status of Second Temple Jewish Literature

None of these Second Temple texts seem to have been designed to be part of the hyper-coordinated scroll collection of the Tanak. But they were designed to be in constant dialogue with the Tanak, and so it’s not surprising that we have evidence of ancient Jewish communities that valued some of these more recent texts as much as they did the Hebrew Scriptures.

In the 2nd century B.C.E., a group of former priests left Jerusalem to live in the hills by the Dead Sea, and they took their library with them. These are the famous Dead Sea Scrolls, among which are many scrolls from the Tanak, along with a wider collection of Second Temple literature. Among the scrolls discovered so far, manuscripts of certain Second Temple texts, such as the books of Enoch or Jubilees, outnumber some scrolls of the Tanak.

Now, because so many of the manuscripts have deteriorated over time, we do not have their whole collection. But what we do have makes it clear that Enoch and Jubilees were special to these Jewish leaders. Does this mean they thought of these Second Temple texts as part of their Scriptures, or at least as texts with divine authority like the Tanak? We don’t know for certain, but it is clear that they held other works in high regard alongside the Tanak scrolls.

The Dead Sea Scrolls provide just one example. But there is evidence of Jewish groups living all around the Mediterranean Sea during these centuries, and the picture is similar throughout. These communities highly valued the Hebrew Scriptures as a word from God, and they also treasured additional texts in a similar way.

Remember that the primary writing technology back then was handwriting on scrolls. The “book,” as we know it, had only recently come into existence and was not yet widespread. So individual biblical books were written on scrolls, which were organized in special storage rooms. The fact that a Jewish community kept their Tanak scrolls alongside additional Second Temple texts may or may not mean that they considered those other scrolls to be “in the Bible,” as it were.

When Jewish authors from this period talk about the contents of their Scriptures (which, surprisingly, they rarely do), they demonstrate awareness of Tanak literature as a unified whole. But scroll technology meant that the boundaries of the collection—what’s in and what’s out—was not the same kind of issue that it is for us today. Once people started putting biblical texts into a codex (the “book,” as we know it), questions about boundary lines intensified.

This helps us better understand Jewish communities of the Second Temple period, who prioritized the Tanak while also possessing and valuing additional Jewish literature written more recently. For some Jewish communities, these texts existed in a kind of “semi-biblical” category. They were not considered part of the Tanak, but they helped Jewish people better understand the main ideas found in the Tanak and, as such, were highly regarded.

Did Jesus and the Apostles Read the Deuterocanon / Apocrypha?

Reading and Quoting Second Temple Texts

When we come to the Messianic Jewish movement sparked by Jesus of Nazareth during the 1st century C.E., we find a similar situation. Following Jesus’ lead, New Testament texts quote from and allude to the Tanak scrolls frequently, often expressing the conviction that God is speaking to his people through these texts.

Jesus marks his quotations from the Scriptures with phrases like “it is written” (Matthew 4:4, Matthew 4:7, Matthew 4:10), or “Scripture says” (John 7:38), or even “God says” (Matthew 15:4). Similarly, the New Testament writers use words like “it says in Scripture” (1 Peter 2:6) or “Scripture says” (Galatians 4:30). Sometimes they highlight the human authors, like Moses or David (see John 5:46 or Acts 2:25), but on other occasions they focus on the Holy Spirit speaking through human authors (see Acts 4:25). Compare Hebrews 3:7 and Hebrews 4:7, which attribute Psalm 95 both to David and the Holy Spirit, suggesting a kind of co-authorship.

So, Jesus and the apostles hold the same conviction about the Tanak that we find in the writings of other devout Jewish people from their time, namely that the Torah, Prophets, and Writings are a word from God to Israel, written by human prophets and scribes. But there is also evidence that they read and valued a broader body of Second Temple Jewish texts.

It’s well known among New Testament scholars that in Romans 1, the Apostle Paul adapts material and themes from Wisdom of Solomon 13-14. A similar case may be found in Matthew 11:28-30, where Jesus picks up key words and images from the Wisdom of Ben Sira 6:23-30 and 51:18-27 and applies them to himself. In Hebrews 11:37 the author references a rather gruesome story about the execution of the prophet Isaiah that is not found in the Hebrew Bible, but you can find it in a Second Temple text called The Martyrdom of Isaiah. These are only three of many examples where New Testament authors draw on a wider body of Jewish literature, some of which is found in the Deuterocanon / Apocrypha.

Ancient Cut, Paste, and Revise Tactics

It’s important to note that for the biblical authors, quoting from Scripture does not always mean reproducing a particular passage word-for-word. Sometimes the apostles quote from Scripture by linking multiple texts together into one. For example, the Gospel of Mark opens with one quotation he attributed to “Isaiah the prophet” (Mark 1:2), but it combines phrases from at least three sources—Isaiah 40:3, Malachi 3:1, and Exodus 23:23.

If we look at James 4:5, things get even more interesting. Here, James quotes a sentence from “Scripture,” but it doesn’t match anything found in the Tanak. The quotation likely originates from a Second Temple Jewish text known as The Account of Eldad and Medad, which retells and interprets a story from Numbers 11. The phrase James quotes is itself a kind of summary of the ideas in Numbers 11:29, but rephrased in a creative way. So James is appealing to Scripture by means of a retelling found in a more recent Second Temple text.

Jude 1:9 alludes to a story about Moses’ death and an argument between an archangel named Michael and “the Devil.” This story appears nowhere in the Tanak, but there are reports from early Jewish and Christian sources that such a story is found in a Second Temple Jewish work known as the Testament of Moses (or Assumption of Moses).

Then, in Jude 1:14-15, Jude explicitly quotes from a Second Temple text connected to Enoch (see Genesis 5:21-24), calling it a “prophecy” that readers should honor. The text of 1 Enoch 1:9 that Jude quotes is itself a combination of quotations from Deuteronomy 33:2, Isaiah 66:15-16, and Zechariah 14:5. So Jude is quoting a hyperlinked chain of Scriptural texts, but he uses 1 Enoch’s way of putting these ideas together.

Apparently, the house churches connected to James and Jude had libraries that included the Tanak along with a wider collection of Second Temple Jewish texts. The role of these additional texts was not to replace the Scriptures but to help people synthesize and coordinate the different parts of the Tanak.

Jewish scribes meditating on the Tanak wrote and compiled these later texts, and their goal was to restate ancient scriptural themes in their new and fast-changing context. They were working to connect key biblical ideas and help people understand their significance, so Jesus and the apostles saw good reason to study and quote from them.

That said, they did not view these texts in the same way as the Tanak. When Jesus and the apostles quote from the Tanak, they often reveal a conviction that these texts are a word from God. But when they quote from or allude to other Second Temple literature, they do not talk about it in the same way. This shows that they distinguished the Tanak as uniquely important, but that distinction did not prevent them from valuing the wider collection of Jewish literature that existed in a kind of “semi-biblical” category.

How Did Different Traditions End Up With Different Bibles?

Early Variations: The Bible in the 2nd and 3rd Centuries

Early Christianity was a diverse and decentralized movement. It began in Jerusalem after Jesus’ resurrection and the gift of the Spirit at Pentecost. As the movement spread across the ancient world, there was no central church governing all the others. Instead, regional church leaders would consult one another when challenges arose, sometimes by holding church councils. A key example of this is the Jerusalem Council described in Acts 15.

This is important for understanding the history of the Christian Bible because there are no records of early Christian councils discussing the contents of the Bible before the 300s C.E. For the first three centuries, as the Jesus movement spread, scriptural scrolls were copied and circulated through house church networks, alongside many other Second Temple texts. So by the 3rd and 4th centuries C.E., Christian communities in different regions of the world had slightly different Bibles.

We have surviving writings from early Christian leaders like Melito of Sardis in the late 2nd century C.E., who traveled to Jerusalem to consult with Jewish communities about the contents of the Scriptures (see Eusebius’ Church History, 4.26.12-14. The list from Melito of Sardis matches the Tanak, except for the curious absence of Esther.

Around the same time, Origen of Alexandria reported a list of texts that he says are regarded as Scripture, “according to the Hebrews,” and his list matches the contents of the Tanak (but not the Tanak arrangement; see Commentary on Psalm 1, 1.1-2). However, the Greek versions of Daniel and Esther that Origen mentions are expanded editions of these books compared to the Hebrew versions found in the Tanak. Origen also notes that there are church communities that value additional texts, such as 1 and 2 Maccabees. And if you look at Origen’s theological writings, you will see how he regularly quotes as Scripture not only writings from the Tanak, but also from the wider body of Second Temple texts, such as Wisdom of Solomon, Judith, and Tobit.

4th-5th Century Debates about the Bible

During the 300s-400s C.E., regional diversity among Christian traditions persisted. In Jerusalem, a bishop named Cyril listed the texts that people in his circles considered Scripture (Catechesis 4.33-36), and it’s similar to a list issued earlier by Athanasius, a bishop in Egypt. These lists primarily align with the books of the Tanak, but Athanasius acknowledges that many churches were also drawing on additional texts for their theological and moral teachings, such as Wisdom of Solomon, Wisdom of Ben Sira, Esther, Judith, and Tobit (Festal Letter 39.4-7).

Cyril uses the term “apocryphal” (a Greek word meaning “hidden” or “set aside”) to describe these texts. He says they should have a “secondary rank” (the Greek is deutero, meaning “second”), and he recommends that Christians should not read them, though he knows that many do.

Athanasius refers to these same texts as “not indeed included in the Canon” (Festal Letter 39.7, but he notes that for centuries they have been used in churches to instruct not only mature believers, but also new converts to Christianity. And, confusingly, when Athanasius uses the term “apocryphal” he is not referring to the additional books named above, but to an even wider collection of Second Temple writings. In other words, even in the late 300s C.E., there was no consensus among the most influential church leaders on which books should be referred to as “Apocrypha.”

In the late 4th century C.E., a biblical scholar in Bethlehem named Jerome had an important back-and-forth correspondence with Augustine of Hippo in North Africa that offers a glimpse into the Christian Bible’s early diversity (see Jerome’s Letter 112 and Augustine’s Letters 28, 71, 82).

Jerome was commissioned in 382 C.E. to translate the Old and New Testaments into Latin, resulting in the “Vulgate” (which means “common”). As one the few Christian leaders who learned Hebrew and studied the Tanak in its original language, Jerome argues strongly for a Christian Old Testament that exactly matches the Jewish Tanak. Although the Vulgate includes the apocryphal books, Jerome recommends that Christians avoid them (see the introduction to his translation of 1-2 Samuel and 1-2 Kings, and his Letter 107.12. And he specifically warns against reading books such as the Wisdom of Solomon, Wisdom of Ben Sira, Judith, Tobit, and 1 and 2 Maccabees.

But Augustine disagrees with Jerome, explaining that Christians in his region have been using an expanded biblical collection for centuries (see On Christian Doctrine 2.8. Augustine’s Bible includes the books of the Tanak translated into Greek, along with Tobit, Judith, 1-2 Maccabees, the Wisdom of Solomon, and the Wisdom of Ben Sira, as well as the expanded editions of Daniel and Esther.

Augustine goes even further by claiming that even if the Hebrew version of the Scriptures was originally shorter and had fewer books, that does not automatically mean that Christians should adopt the Hebrew Bible (see City of God 18.43. Rather, he thinks that the Holy Spirit must have been the author of the expanded Greek Bible for the church. Surely God would not allow followers of Jesus to develop and read a “wrong” Bible for over 300 years. If the Greek Bible is expanded, he concludes, it must be God’s will.

From Early Manuscripts to a Bible in the 16th Century

The diversity of early Christian Bibles is also apparent in surviving codex Bibles from the 4th and 5th centuries C.E. that have survived. In 313 C.E., Emperor Constantine legalized Christianity, and it eventually became the Roman Empire’s official religion. Christian scribes had more resources than ever before, allowing them to produce lavish editions of the Scriptures, some of which still exist.

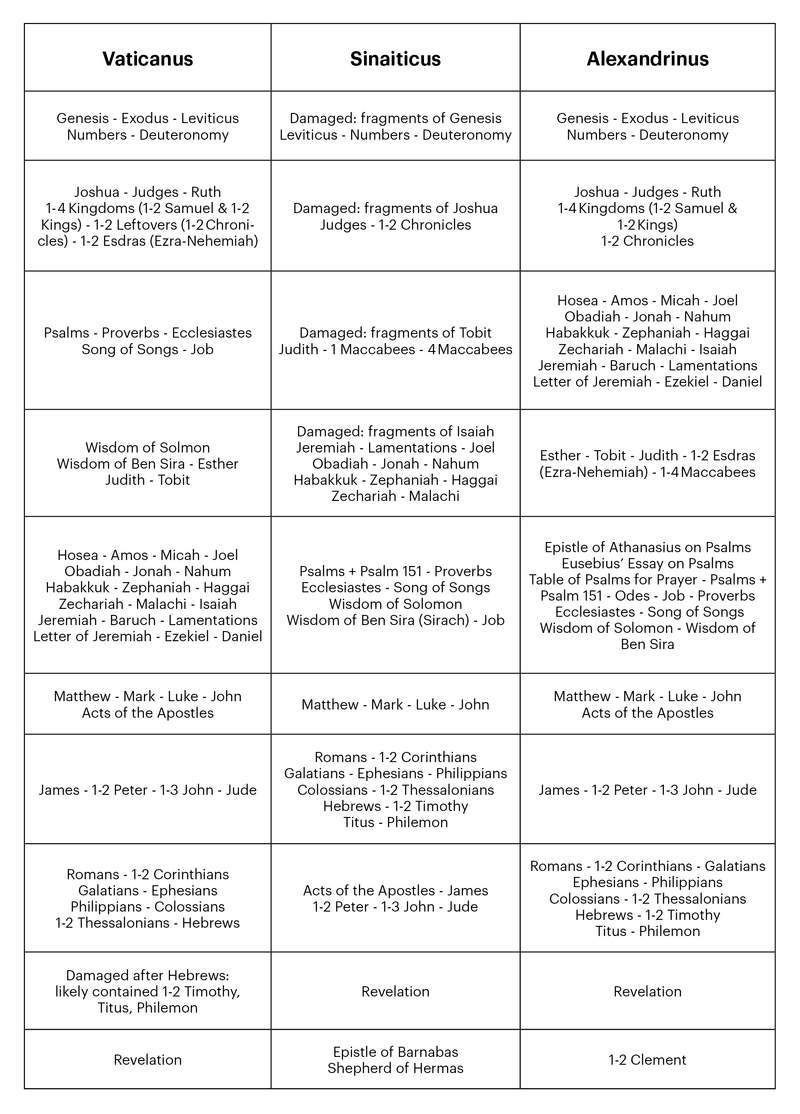

The three examples below—Vaticanus, Sinaiticus, and Alexandrinus—are among the most ancient Greek Bibles (called “codices,” the plural of “codex”) and their tables of contents reveal a surprising diversity:

(View below image in a new window.)

All of these codices contain a broader Old Testament that includes additional Second Temple texts, and their versions of Daniel and Esther are expanded second editions that have material not found in the original Hebrew. Also notice the additional books in the New Testament (Epistle of Barnabas, Shepherd of Hermas, 1-2 Clement). Even the boundaries of the New Testament collection were still being debated during these centuries.

Jerome’s Vulgate translation became the most widely used Bible in Latin-speaking Catholic Christianity and stayed that way for the next 1,200 years. In the Greek-speaking world, Christians continued to use the older Greek translation of the Tanak known as the Septuagint (or LXX). The Septuagint and Greek New Testament spread throughout Eastern Orthodox Christianity and formed the basis for many translations into the languages of the Orthodox churches, such as Russian, Armenian, and Egyptian.

Since most Christian leaders during these centuries did not know Hebrew, the precise content and shape of the Hebrew Tanak was largely forgotten. Latin and Greek Bibles both had an expanded Old Testament when compared to the Tanak, but people didn’t see this variety as problematic. It was simply an accepted reality.

Gutenberg’s Press and the First Protestant Bibles (Which Include the Apocrypha)

Several major historical events during the 15th and 16th centuries sparked a flurry of change and controversy surrounding the Bible. Around 1440, Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press, and Bibles were among the first books printed. Around the same time, European universities saw a rise in the academic study of ancient texts. And as Christian scholars started learning biblical Hebrew in unprecedented numbers, the idea of reading the Tanak in its original language gained traction.

Then, in the mid 1500s, the Protestant Reformation ignited fierce debates between Protestant and Roman Catholic leaders, often centering on biblical interpretation.

Initially, both Catholic and Protestant leaders used Bibles that included an expanded Old Testament. When Martin Luther, the figurehead of the Reformation, translated the Bible into German, he included the additional Old Testament books in an appendix titled “Apocrypha.” The same was true for early English translations, such as the Geneva Bible of 1560 (brought to the American colonies on the Mayflower) and the King James Bible of 1611.

However, tensions between Protestants and Roman Catholics escalated during the 1600s. And when disputes involved texts from the Apocrypha, their inclusion in the Bible became increasingly contested by Protestant leaders.

One notable example arose from the Roman Catholic Church’s sale of indulgences to Christians who wanted to pray for the forgiveness of deceased loved ones. This practice was sometimes explained with reference to a ritual mentioned in 2 Maccabees 12:43-45, which raised suspicions among Protestant leaders. They not only rejected the practice but also pointed out that 2 Maccabees was not part of the original Hebrew Bible—which is technically true. But it was also true that 2 Maccabees had been a part of the expanded Christian Bible for nearly 1,500 years.

Controversy flared, and these Protestant leaders argued that Christian doctrine should be based solely on the original-language versions of the Old and New Testaments, not on the Latin translation or any books from the Apocrypha. Over time, some Protestants began to view the apocryphal books as dangerous, likely due to their association with these controversies.

In response, the Roman Catholic church officially affirmed the expanded Old Testament as Scripture at the Council of Trent (1545-1563 C.E.), leading to the description of these additional books as “Deuterocanon” (Latin for “Secondary Canon”). This term, which is actually much older than the Council of Trent, became associated with the Catholic Bible. The other ancient name for these texts, “Apocrypha,” was taken over by Protestants and came to have a negative connotation.

By the late 1600s, Protestant English Bibles began omitting the Apocrypha entirely. As a result, these books became mistakenly associated with the Roman Catholic Church, and their Jewish origins and importance to early Christianity were largely forgotten.

Should Christians Read the Deuterocanon / Apocrypha?

We are now more than 400 years removed from those developments. As a result, many Christians today are unfamiliar with the original Tanak arrangement of the Hebrew Scriptures, and many Protestants have not had the opportunity to read or explore the books of the Deuterocanon / Apocrypha.

Different Christian traditions hold varying views on these texts. Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches have long used an expanded Old Testament, with the Catholic Church officially recognizing these books as Scripture under the term Deuterocanon. In contrast, Protestant tradition affirms only the Hebrew Bible and the Greek New Testament as authoritative for Christian theology and practice.

These differences are significant and deserve thoughtful attention. BibleProject’s goal in sharing resources on the Deuterocanon / Apocrypha is not to promote one tradition over another, but to help Christians of all backgrounds understand the important role these texts have played in the church since the time of Jesus and the apostles.

For 2,000 years, Christians have read and studied these writings. They offer insight into how Second Temple Jews—including Jesus and his earliest followers—understood the Hebrew Bible, and they illuminate Jewish culture under Greek and Roman rule, the world in which the New Testament was written.

Even if Christians disagree on the canonical status of these books, they can agree that these texts have been valuable to followers of Jesus for centuries, and studying them can enrich our understanding of Scripture today.

Recommended Resources

• BibleProject Video Series: The Deuterocanon / Apocrypha

• BibleProject Podcast series: How the Bible Was Formed

• Michael Coogan, ed., The New Oxford Annotated Apocrypha, 5th edition.

• John H. Sailhamer, How We Got the Bible.

• Paul Wegner, The Journey from Texts to Translations: The Origin and Development of the Bible.

• Siegfried Meurer, ed., The Apocrypha in Ecumenical Perspective.

• Edmon Gallagher and John D. Meade, The Biblical Canon Lists from Early Christianity.

• James C. VanderKam, An Introduction to Early Judaism.