What Does Jeremiah 29:11 Mean? (“For I Know the Plans I Have for You”)

Explore a Prophet's Offer of a Different Kind of Hope

Imagine a packed auditorium. Graduates sit in neat rows—their caps balanced, gowns pressed. The speaker at the podium clears her throat, smiles at the sea of expectant faces, and begins:

“Jeremiah 29:11 says, ‘“For I know the plans I have for you,” declares the LORD, “plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future”’” (NIV).

It sounds like the perfect verse for a day like this, full of promise and expectation. However, when we look deeper into the context from which Jeremiah wrote these words, we find that he offered them in a dark and brutal context.

The people who first heard these words were not standing at the threshold of success—they were drowning in despair. And the verse’s broader literary context presents a paradoxical message of life in the land of death and peace for a warring empire.

So do Jeremiah’s words bear any relevance for us today? What is Jeremiah 29:11 really saying?

By exploring the verse’s historical background and literary context, we can uncover a more complex and compelling message about God’s purpose for your life. Rather than a naive promise of immediate prosperity, these words are a call to faithful endurance in exile, where life and peace come through active participation in God’s redemptive work. Jeremiah 29:11 is not a promise of an easy path but an encouragement that God’s plans are ultimately good. We can trust that he will one day fulfill his promise to bring us out of hardship as we participate with faithful endurance in his long, slow work of restoration.

Jeremiah’s Shocking Instructions

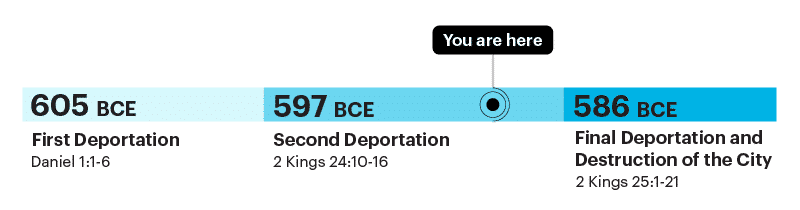

Jeremiah 29:11 is found in a part of the scroll of Jeremiah containing letters sent by the prophet Jeremiah to Israelites living in Babylonian exile. At the time of his writing, Jerusalem and the temple had not yet been destroyed, but the Babylonians had already attacked Jerusalem twice and deported many Israelites (in 605 and 597 B.C.E.; see Dan. 1:1-6; Jer. 29:1-2).

Those who received these letters had endured the horrors of war, the destruction of their homes, and a forced deportation into a foreign land. We can imagine that the pain of their deportation would have been particularly stark because their very identity was rooted in their land, a gift from God after a miraculous exodus from Egyptian captivity.

The people find themselves torn from their inheritance, banished from the land of promise, and thrust back into the house of bondage. If the exodus and entry into the promised land were acts of creation and new life, then exile is de-creation, a return to chaos and descent into the realm of death. Exile is not just a geopolitical catastrophe—it’s a cosmic unraveling (see Jer. 4:23-26). Israel’s story of liberation from Egypt has been reversed. They were once one people gathered into the promised land, but now they have been scattered like dust.

Go Deeper: Watch this video to learn more about the biblical theme of exile.

The prophet Jeremiah begins his letter with a surprising message. He doesn’t promise that all will soon be well; rather, he instructs people to plan on remaining in exile for the long haul.

Jeremiah 29:5-6, BibleProject Translation

Build houses and live them,

plant gardens and eat their fruit.

Take wives and beget sons and daughters.

Take for your sons wives,

and your daughters give to husbands

so that they may bear sons and daughters.

Multiply there and do not decrease.

Jeremiah’s instructions must have been shocking to the people. Build houses? Settle down? They want out of this mess, not a longer stay. Also, they’ve previously heard better, more appealing prophetic reports. Before his death, the prophet Hananiah boldly declared that the exile would last only two years (Jer. 28:1-4). If deliverance is just around the corner, why should they prepare for the long haul?

But Jeremiah encourages the people to discern between reality and manipulative false prophecies: “Do not let your prophets who are in your midst or your diviners deceive you” (Jer. 29:8, NASB). Jeremiah speaks the truth—and he’s already announced that the exile will persist for seven decades (Jer. 25:11-12), far beyond the quick restoration that people desperately want to believe. Since Israel has to face a prolonged stay in Babylon, Jeremiah challenges his readers to abandon wishful thinking and instead see their situation in a new light.

Be Fruitful and Multiply in Exile?

Jeremiah instructs the exiles in Babylon to live out God’s original design, echoing his commands to the humans at creation: “Be fruitful and multiply” (Gen. 1:28). The language of building houses and planting gardens also appears in Isaiah’s vision of new creation (Isa. 65:21). However, Jeremiah’s readers are not in the lush garden of Eden or in the new Heaven and Earth imagined by Isaiah, where there is no memory of weeping or pain (Isa. 65:19). Through Jeremiah, God is calling the people to live as agents of creation—to live like they’re in the garden—even while they’re in exile. And he upends their expectations by suggesting they should also seek peace for their enemies.

Jeremiah 29:7, BibleProject Translation

But seek the peace of the city where I have exiled you

and pray on its behalf to Yahweh,

for in its peace there will be peace for you.

There Was No Peace in Jerusalem

The Hebrew word for “peace” (shalom) signifies not just the absence of conflict but also a state of completeness and wholeness; it represents integrity, harmony, and mutual well-being.

Before the Babylonian invasion, shalom was the favorite word of the false prophets in Jerusalem. These smooth-speaking “prophets” preached a message of optimism, declaring that things would soon get better. Like those who spout platitudes to suffering people, they offered positivity without substance. They promised God’s divine blessing and protection without requiring care for the vulnerable. And their false message reinforced the power of the elite, who were invested in maintaining their status at the expense of others.

Jeremiah’s call to plant and build in Babylon starkly contrasts with the destruction that uprooted Israel from its homeland, fulfilling his prophetic calling “to uproot and tear down, to destroy and overthrow, to build and to plant” (Jer. 1:10, NIV).(1) The juxtaposition of destruction and creation in these words works to expose the suffering and injustice infecting the land—the rot must be removed for the people to flourish.

Israel’s leaders used faith language to justify oppression, invoking shalom while perpetuating violence (Jer. 6:14). The very institutions meant to uphold justice—the temple, the monarchy, and the priesthood—had become instruments of exploitation. Israel’s leaders had abandoned their covenant relationship with God and were even practicing child sacrifice (Jer. 7:31). In the words of Old Testament theologian Walter Brueggemann, “The system is under judgment and has failed. It may mouth shalom, but it embodies terror.” (2)

In the midst of all this darkness and exile, Jeremiah 29 offers, for the first time in the scroll, the possibility of true shalom. Paradoxically, the people will find peace, well-being, and wholeness when they seek these things for the warring city that has shattered Jerusalem, when they learn to love those they’ve been taught to hate.

The plan God has for their lives is aimed at transforming them into people who know that shalom is neither self-serving nor self-determined; it is experienced in actions that seek the good of others, even our enemies.

Hope for Endurance

Jeremiah’s call to settle in Babylon and make peace there is not the end of his message. He also offers assurance that exile will not be permanent. In Jeremiah 29:10, the prophet declares that after 70 years, God will visit his people and bring them back to their homeland, setting the stage for our well-known verse.

Jeremiah 29:11, BibleProject Translation

“For I know the thoughts that I am thinking about you,”

declares Yahweh,

“thoughts for shalom and not for evil

to give you a future and hope.”

Unlike an audience of graduates imagining a season of prosperity, the exhausted exiles first hearing these words were facing a time of devastating suffering. When God speaks of shalom through Jeremiah, his promise contains no sentimental fluff or naive optimism. The hope Jeremiah writes about comes with a challenge, and part of that challenge includes a trust in God so deep that it will reframe the people’s understanding of reality.

Common sense might tell them that, due to their many crimes, God has simply turned away and abandoned them. But “I know the thoughts that I am thinking about you” suggests God’s presence, attunement, and attentive concern for them. The people might also conclude that God wants to hurt them, but God’s plan is “for shalom and not for evil,” suggesting that their suffering comes out of a desire not for retributive harm but for transformative good. Change often hurts. God is restoring the exiles to be humans compelled by love—a love so strong that it seeks the shalom of their captors.

In Babylon, the prophetic challenge must be lived. It must be truly embodied to bring flourishing and renewal, not just for the exiles but for the very empire that shattered their world. The exiles face a choice: Will they continue clamoring for fake peace, or will they embrace true peace by seeking the good of the brutal empire that displaced them? Platitudes and pretend shalom numb them to reality. Truth-telling and real shalom requires faith, patience, and a radical trust in God’s unfolding plan.

Trusting God in Exile

Jeremiah offers a hope that doesn’t erase suffering but transforms it. With each new tree planted and new child born, the people will experience God’s creative care. They are not home, and that’s painful, but as they learn to cultivate peace in the land of their enemies, they will experience the fruits of restoration.

In the Bible’s Prophetic Literature, hope never involves a denial of suffering. Instead, it’s grounded in trust in God’s presence, even in the darkest moments. For Jeremiah’s audience, every house they build, every garden they tend, every prayer they offer for Babylon’s welfare is an act of trust—a living hope in God’s promise that their story is not over.

When searching for Bible verses about God’s plan for our lives, we may encounter Jeremiah 29:11 used as a feel-good slogan, a promise of personal prosperity detached from its historical and literary context. But by imagining that these words promise an easy path forward or a vision of personal success for the future, we might accidentally imitate the false prophets who naively promised things they could not ensure. We might turn shalom into a platitude that masks reality and ignores the complexities of suffering in our midst. And if we do that, we could end up moving further away from the real shalom that comes from aligning with God’s plan for all humanity to participate in his long, patient work of restoration.

Jeremiah sheds a new light on what real hope looks like. To embrace the promise of Jeremiah 29:11 is to step into this paradox: Peace comes not from escaping hardship but from seeking the good of others, our enemies included, and trusting that God is always creating life in the midst of our suffering.

- Abraham J. Heschel, The Prophets (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2001), 156.

- Walter Brueggemann, A Commentary on Jeremiah: Exile and Homecoming (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998), 193.